The labor camps represent a form of administrative repression of the communist state, under which people were deprived of their freedom by decision of the Ministry of the interior (MoI), without a trial, without the right of legal defense, without a specific charge and without a set term of imprisonment. Labor camp prisoners didn’t know what the charge against them was or when they would be released. The MoI used the labor camp interment for repressions against various political, civil, social and religious groups (in the absence of an actual committed crime that people could be charged for), but also when an urgent general repression was needed.

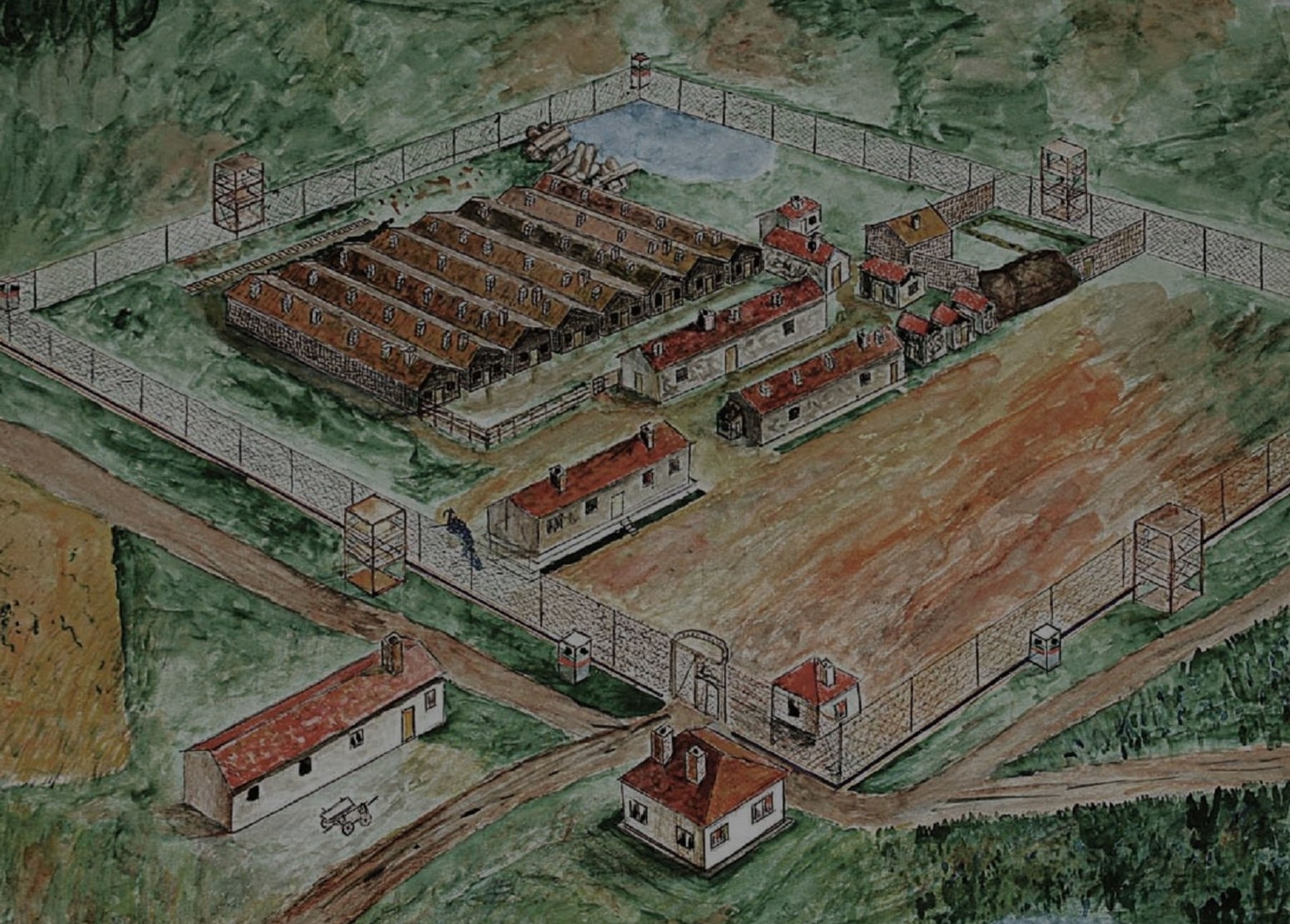

The Belene camp was one of dozens of such camps in communist Bulgaria. Its special significance is explained by Borislav Skochev, author of the most extensive study of the camp – The Belene Concentration Camp 1949-1987:

“I once found it an injustice of historical memory that the Belene concentration camp has become a symbol of the communist repression, while the names of the dozens other concentration camps, which were also “the truest showcase of socialism” […] have more or less sunk into the mists of oblivion. Already at the start of my research, I knew that there is logic and justice in that. Belene was neither the first, nor the last communist concentration camp, but it existed for longer than the other camps, from 1949 until 1987, almost without interruption.

The geographic location of this island, separated from Bulgaria by the powerful waters of the Danube, sheds light on the experience of several generations of internees and the feeling that they were uprooted from their home country, written off by the world of the living. The communist authorities themselves to the end of the regime purposefully used the name “Belene” as a symbol of threat.” - The Belene Concentration Camp 1949-1987 by Borislav Skochev (2017)

It is in the courage of those who opposed the regime that our freedom today finds its hope and justification.

Belene is a truly beautiful place. The islands around Belene are home to hundreds of birds, and the Persina nature park in the backdrop of the setting sun and the golden Danube are breathtaking. The ancient customs building reminds us of the richness and fertility of the Bulgarian land.

But here lie buried the pain and trauma of the entire Bulgarian society from the years of the communist regime. Belene is the site of the largest and longest-lasting communist camp. Here, thousands of people were subjected to forced labor, violence and humiliation without having committed a crime - without a trial and without a sentence. Some of them never left Belene.

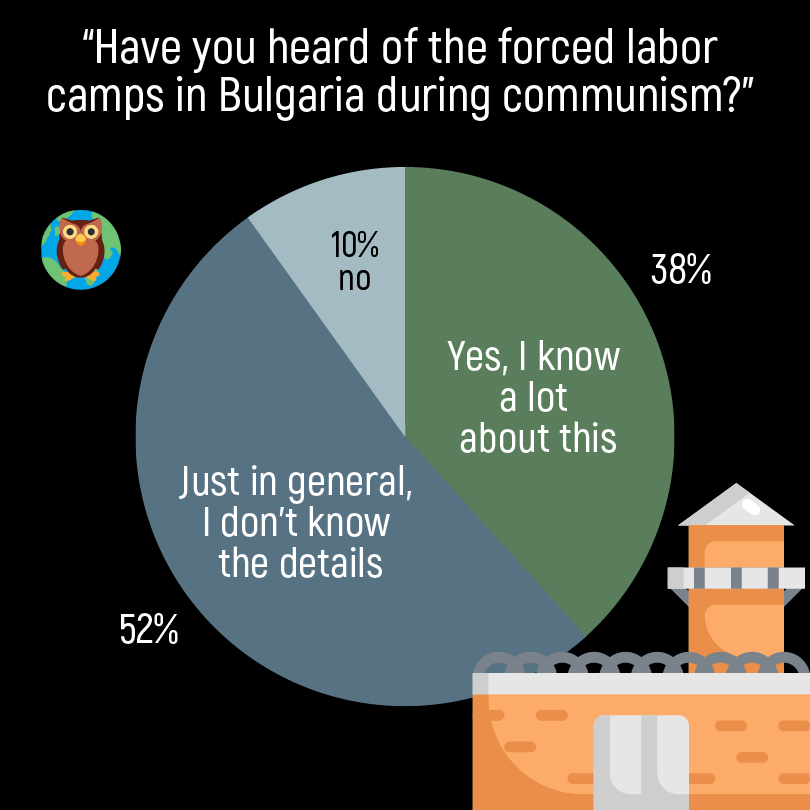

In order to look forward, we need to be able to look backward, into our past. When it is close to the present day, it is especially painful, because our parents and grandparents are part of it. Some of them were victims, while others were directly involved in the crimes of the communist regime. But most of them were neither victims, nor hangmen. And they were not interested in what was happening in Belene, neither then, nor now. Knowledge is freedom.

It is in the courage of those who opposed the regime that our freedom today finds its hope and justification.

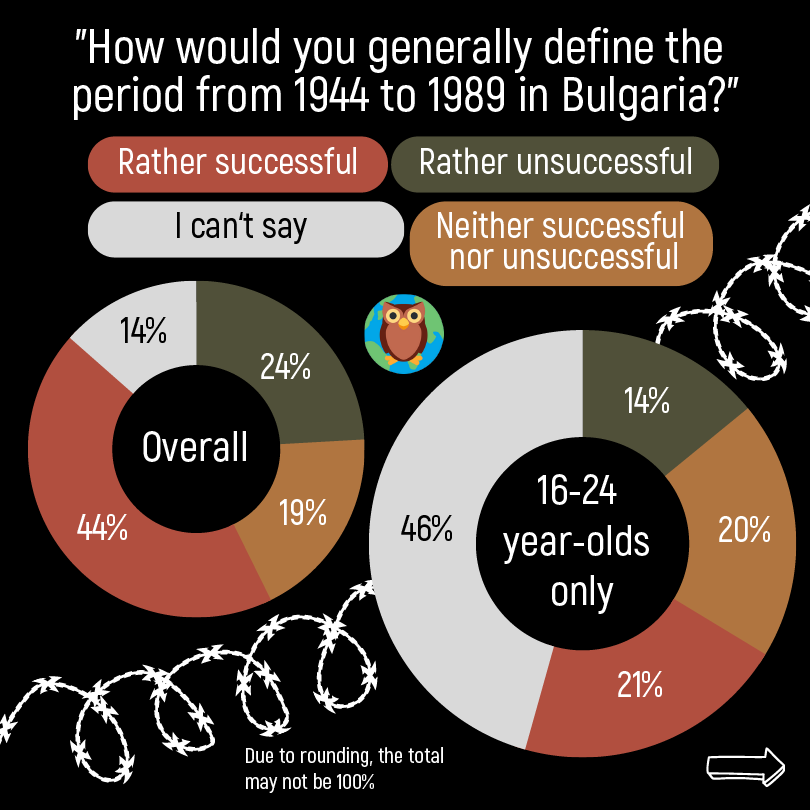

The communist regime in Bulgaria lasted 45 years (1944-1989). Thousands of executions, thousands of imprisonments in labor camps without trial and sentence, several bankruptcies of the state – these are only some of the “achievements” of this totalitarian regime.

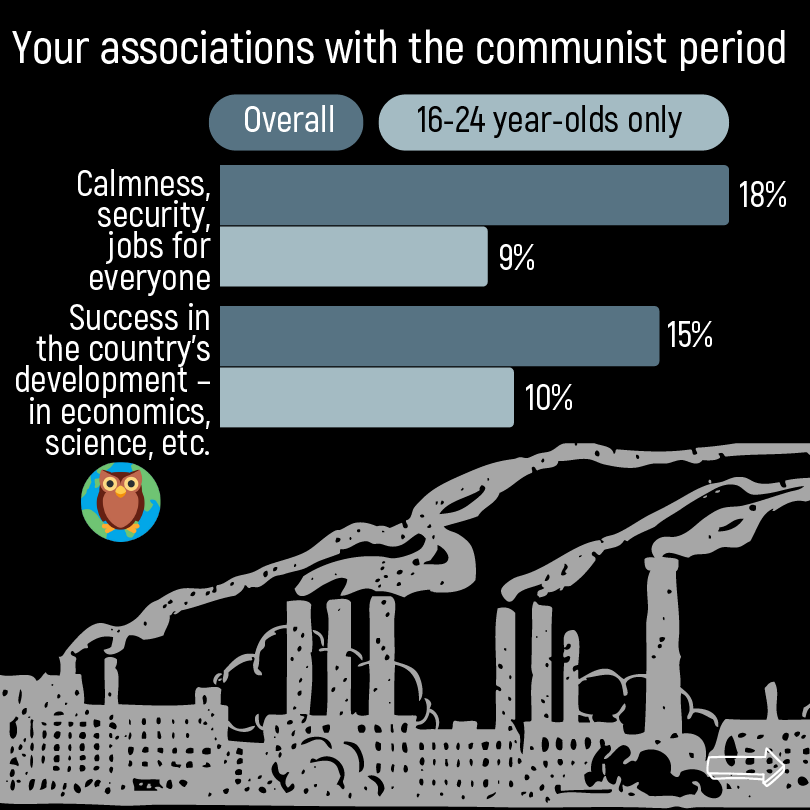

In the present day we still live with the propaganda myths of the regime – for the good old times or the role of the Soviet Union as Bulgaria’s big, selfless brother.

This is why we make the survivors of the labor camps visible to society. We realize that it is in the courage of those who opposed the regime that today’s freedom finds its hope and justification.

In the present day we still live with myths from the propaganda of the communist regime.

In the present day we still live with myths from the propaganda of the communist regime.

Създаването на широка и всепроникваща агентурна мрежа е съществена и необходима част от тоталитарната система на пълен контрол. Вербовката на агенти от „вражеските среди“ става главно чрез принуда, особено през първите 15 – 20 години на комунистическия режим. По тази тема в края на 1946 г. началникът на отдел „Държавна сигурност“ (ДС) Димо Дичев казва: „Ние не сме се научили да използваме по-гъвкави начини за спечелване на сътрудници, освен този на откритата принуда [...]“. (Доклад за организацията и дейността на отдела. АКРДОПБГДСРСБНА – М, ф. 1, оп. 1, а.е. 219.)

Today’s vocabulary, using terms such as ‘agents’ and ‘collaborators,’ fails to capture the existential hopelessness faced by the camp internees—the coerced 'voluntary' agreement made in the liminal space between hunger, fear, and the hope of protecting their loved ones.

4 years and 4 months in labor camps

Offense: anarchist

9 months under arrest and in a camp

Offense: son of a provincial governor in the Kingdom of Bulgaria

42 days in the Sunny Beach camp near Lovech

Offense: "hooligan", son of a member of the opposition

9 months under arrest and in a camp

Offense: an attempt to escape from Bulgaria

2.5 years under arrest and in a camp

Offense: participant in the anti-communist resistance

3 years under arrest, in a camp and prisons Offense: Agrarian, member of the opposition

3 years and 1 month under arrest and in and political prison

Offense: participant in the anti-communist resistance

In 1961, Zheko was sentenced to death for resistance to the communist authorities. Subsequently, his sentence was changed to lengthy imprisonment.

In 1964, Zheko Stoyanov received an amnesty and was released from the Stara Zagora prison. In order to earn his living, he did hard manual labor, working as a porter, a painter on construction sites, and a miner. For twenty-two years he worked in underground mines.

After the democratic transition of 1989, Zheko Stoyanov entered politics and in 1997 he was elected a member of parliament for the United Democratic Forces. At the age of sixty, he completed a degree in economics.

2 years and 8 months under arrest and in political prison

Offense: dissemination of anti-communist leaflets

After 1958, Alfred was granted the right to travel to Bulgaria, where he spent his summer holidays. There he got to know the new reality of the country and met other like-minded individuals who were dissatisfied with the regime and with whom, in 1968, he distributed printed leaflets against the Communist Party.

Arrested on August 28, 1968, for the distribution of these leaflets, Alfred was sentenced as a spy to fifteen years in prison, of which he served three in the Stara Zagora prison. Following diplomatic pressure, he was released on April 30, 1971, and left Bulgaria. He later returned to illegally take his beloved out of the country, succeeding through a complex and risky plan.

After settling in France, Alfred actively collaborated with groups fighting for human rights in Bulgaria and helped illegally take other political prisoners out of the country. He currently lives in Sofia.

Four years in camps and in forced resettlement

Offence: disagreement with the change of Turkish names to Bulgarian