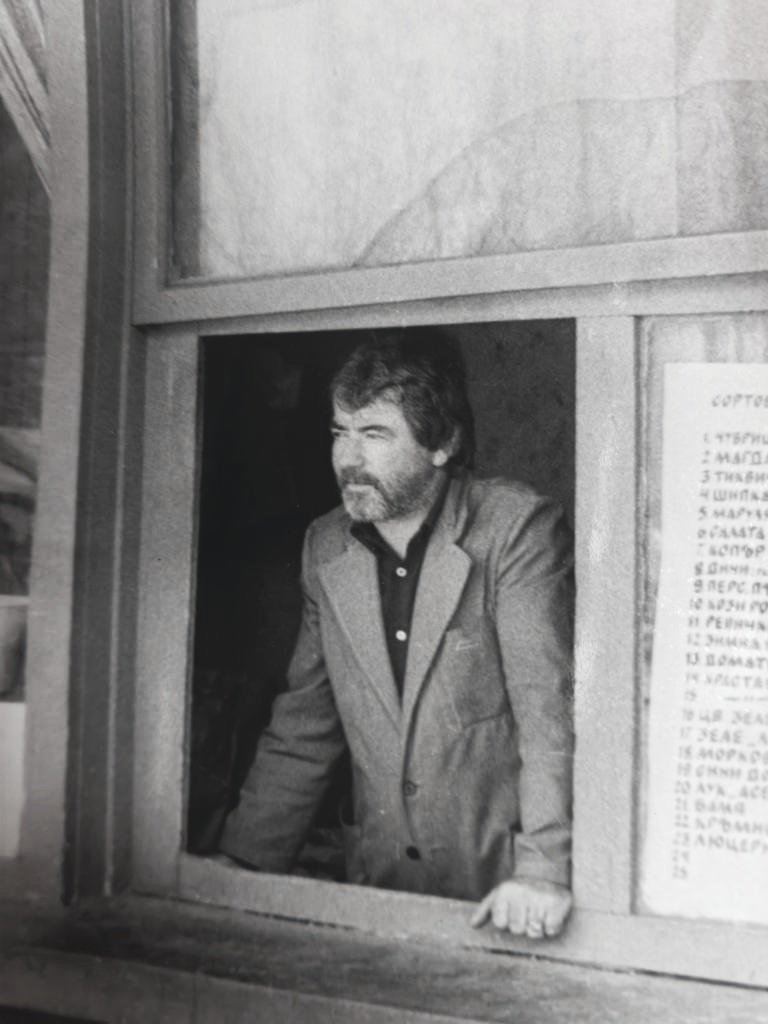

42 days in the Sunny Beach camp near Lovech

Offence: hooligan, son of a member of the opposition

… what am I doing here at this old age and why did God pick only me among the internees at this camp to survive and live on for these many years? To be now in front of you and tell you about the “flourishing of communism” ...

Kolyo Ivanov Vutev was born on September 10, 1940, in the village of Toros, near Lukovit, in a family engaged in agriculture. Before the changeover to the totalitarian regime, his grandfather was mayor of the village, highly approved and re-elected over 28 years by the locals. Initially, Kolyo’s father was apolitical but after he refused to join in the collectivization and to hand over his land to the new authorities, the entry door of the family home was chopped into pieces with an axe and the sign “kulak”, a term used to chastise peasants who withheld grain, appeared overnight.

Another contributing factor for their proclamation as “enemies of the people” was that Kolyo’s uncle was an adherent of Nikola Petkov’s, one of the leaders of the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union. Kolyo’s uncle was the first person arrested in the family and he was sent to the Belene labor camp. He spent the next seven years and seven months in different labor camps.

It was only on Saturdays that they didn’t murder internees – on Saturdays and Sundays, because for most of the camp guards there were days of rest, but for us – there were none.

After his family was denounced by the new authorities, Kolyo was not allowed to continue his education in the vocational school of forestry in Teteven and he returned home. There he began work as a baker and started his sporting career as a wrestler under the tutelage of Hari Stoev. In 1959, when Kolyo was 18 years old, he took part in an altercation and a fight, following which he was not admitted to an evening entertainment event of the Komsomol, the Communist Union of Youth. The following morning, he was arrested and taken to the quarry near Lovech, infamously known as the Sunny Beach labor camp – the camp with the harshest regime and most brutal history in Bulgaria’s recent past.

The Sunny Beach labor camp was set up in 1959 with a decree by Mircho Spasov, Deputy Minister of the Interior, following the temporary closure of the Belene camp, from where 166 political prisoners deemed dangerous to the communist regime were transferred. There were no formal procedures for the running of the camp and there was no official documentation establishing the camp; it was a place ruled by violence and arbitrary acts. For the three years of its existence, more than 1,500 people were sent to the Sunny Beach labor camp – agrarians, opponents of the regime, young people who were deemed hooligans, and other innocent Bulgarians who were interned there without trial or sentence. Until its closure at the beginning of April 1962, according to official data, 155 people were murdered or died following torture or backbreaking labor. According to unofficial testimony of numerous survivors the dead were many more.

At about 12.15 pm they would bring fish soup, but fish soup made of the heads of the fish. If anyone got a whole head, it was as if they had won the jackpot.

Kolyo Vutev was interned without any administrative procedure, as he put it in his own words, as a “hooligan” with a “rebellious temperament and sense of humor”. He spent just 42 days at the Sunny Beach camp, during which time he witnessed brutal and sadistic murders and torture on a daily basis. “It was only on Saturdays and Sundays that they didn’t murder internees”, said Kolyo. A fellow internee was shot dead right in front of him for reaching out across the barbed wire fence to grab scraps of food. On Kolyo’s first night at the camp he witnessed how one of the most dangerous guards, Shaho, entered the sleeping dorms and killed two internees. The assigned labor was beyond the strength of many and those who couldn’t meet the daily work quota were shot dead on the spot.

Kolyo Vutev was released from the Sunny Beach labor camp because of sport. He was given leave just for one competition, but, following his win, during the medal presentation by Tseno Tsenov, Secretary of the Bulgarian Wrestling Federation, he burst into tears. Tsenov found out where Kolyo came from immediately prior the competition and took him under his tutelage, acting as his guarantor. Kolyo was free, but he could not mention to anyone where he had been or what he had seen. If questioned, he had to say that he had been away at sports camp. His mother heard that her son had been in a labor camp from a neighbour, while his father never found out.

4 years and 4 months in labor camps

Offense: anarchist

9 months under arrest and in a camp

Offense: son of a provincial governor in the Kingdom of Bulgaria

42 days in the Sunny Beach camp near Lovech

Offense: "hooligan", son of a member of the opposition

9 months under arrest and in a camp

Offense: an attempt to escape from Bulgaria

2.5 years under arrest and in a camp

Offense: participant in the anti-communist resistance

3 years under arrest, in a camp and prisons Offense: Agrarian, member of the opposition

3 years and 1 month under arrest and in and political prison

Offense: participant in the anti-communist resistance

In 1961, Zheko was sentenced to death for resistance to the communist authorities. Subsequently, his sentence was changed to lengthy imprisonment.

In 1964, Zheko Stoyanov received an amnesty and was released from the Stara Zagora prison. In order to earn his living, he did hard manual labor, working as a porter, a painter on construction sites, and a miner. For twenty-two years he worked in underground mines.

After the democratic transition of 1989, Zheko Stoyanov entered politics and in 1997 he was elected a member of parliament for the United Democratic Forces. At the age of sixty, he completed a degree in economics.

2 years and 8 months under arrest and in political prison

Offense: dissemination of anti-communist leaflets

After 1958, Alfred was granted the right to travel to Bulgaria, where he spent his summer holidays. There he got to know the new reality of the country and met other like-minded individuals who were dissatisfied with the regime and with whom, in 1968, he distributed printed leaflets against the Communist Party.

Arrested on August 28, 1968, for the distribution of these leaflets, Alfred was sentenced as a spy to fifteen years in prison, of which he served three in the Stara Zagora prison. Following diplomatic pressure, he was released on April 30, 1971, and left Bulgaria. He later returned to illegally take his beloved out of the country, succeeding through a complex and risky plan.

After settling in France, Alfred actively collaborated with groups fighting for human rights in Bulgaria and helped illegally take other political prisoners out of the country. He currently lives in Sofia.

Four years in camps and in forced resettlement

Offence: disagreement with the change of Turkish names to Bulgarian