9 months under arrest and in a camp

Offense: son of a provincial governor in the Kingdom of Bulgaria.

The camps were one of the most powerful factors for creating the phenomenon which the more courageous dissidents called “homo sovieticus” – a creature that has either forgotten what its natural human rights are, or it never learned that it had such rights.

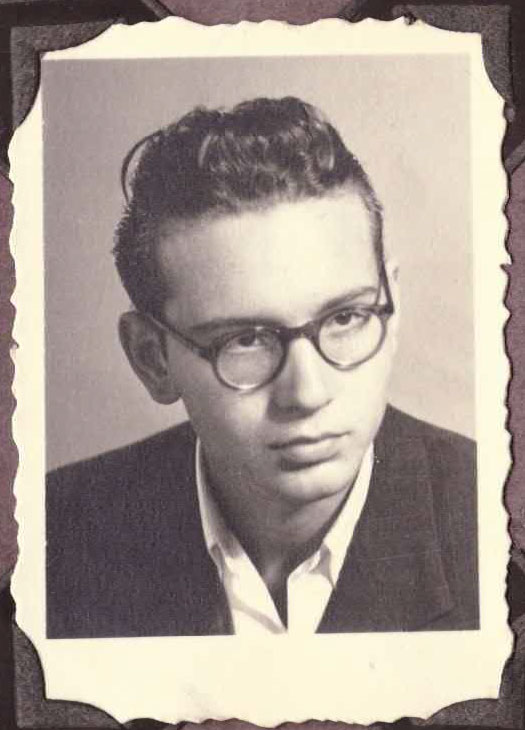

Nikola Daskalov was born on September 8, 1934, in Sofia. His father, Dimitar Daskalov, was a provincial governor of Plovdiv and of Xanthi in the Kingdom of Bulgaria. After the communists came to power, his father was arrested, badly abused and subsequently sentenced to death by the Communist People's Court. He was executed by firing squad on February 10, 1945, and Nikola and his mother were forcibly resettled from Sofia for nearly ten years.

Together with his mother and grandmother, Nikola settled in his father’s home village of Golyama Brestnitsa, near Teteven. He attended the local high school, but he was placed on an “enemy list” and expelled shortly before graduating.

Marked by the communist authorities, agent provocateurs were sent to try set Nikola up, which became the formal reason for his arrest in 1952. Taken from a bus stop in Teteven and sent away for supposedly a brief check, Nikola spent the next four months under arrest and investigation, following which he was sent to the forced labor camp in Belene.

The camps were one of the most powerful factors for creating the phenomenon which the more courageous dissidents called “homo sovieticus” – a creature that has either forgotten what its natural human rights are, or it never learned that it had such rights.

A committee set a term of “re-education” in a camp for three years, of which Nikola spent five months and ten days on Persin Island. He was released early during the mass amnesties following the death of Stalin. After his release from the camp, Nikola was engaged in low-skill labor, taking any job he found, including excavation and concrete-setting work and truck-driving. After nearly ten years in forced resettlement, Nikola’s family was able to return to Sofia where he found better jobs working as a photographer and in different state institutes. Nikola was recruited by State Security at the age of 18 while he was interned in Belene. In a series of interviews as well as in his testimony here he openly talked about State Security’s repression and the trauma of those recruited by State Security.

After the fall of the communist regime, Nikola was an active participant in public and political life, taking up positions such as deputy-minister, municipal councillor and secretary of Sofia Municipality. He published his memoirs in the volumes There Are No Oases In the Red Desert and The Glorious Time.

Nikola Daskalov passed away on January 15, 2025, at the age of ninety.

“When my daughter was born and about the time she was 4-5 years old, I felt a big dilemma form in me – should I say nothing on the society topic and let my child be brainwashed and become a half-idiot by participating in the pioneer movement, the Komsomol [the Leninist Young Communist League], you name them. Or should I start opening her eyes, in which case I would put her at risk? Being a child, she would tell others what she learned from me and she would ruin her life. And as I was wondering, at the time when she was 8 years old, she asked me the following question “Is it true that we don’t need this subway system, but the Russians are making us build it?” I asked her, “How do you know these things?”. And she said, “Well, kids outside talk about it.” I told her, “Slavena, I will now tell you what the situation is, however, you shouldn’t talk about this much as you would be in trouble.” And she exclaimed, “Ah, father, I know what should be said at school and what should be said in front of strangers!" – Half of me was extremely satisfied. And at the same time, I was horrified. This regime had already turned an eight-year-old child into a perfect hypocrite, into a double-dealer.”

… communism is so paradoxical that it is not possible to describe it fully… It is difficult to decide what to talk about and what to put aside as non-essential.

You can find out more about Nikola and his memories of the communist regime and the Belene camp by scrolling up and asking him a question.

-------

The testimonies published here present survivors’ personal memories and accounts and reflect their individual experiences. They do not substitute professional historical research and may contain inaccuracies.

Sources: Daskalov, Nikola, There Are No Oases In The Red Desert, Ciela Publishing House, 2014; interview from the Oral History archive of the Institute for the Study of the Recent Past”; photo story Histories from Belene available at:

… communism is so paradoxical that it is not possible to describe it fully… It is difficult to decide what to talk about and what to put aside as non-essential.

4 years and 4 months in labor camps

Offense: anarchist

9 months under arrest and in a camp

Offense: son of a provincial governor in the Kingdom of Bulgaria

42 days in the Sunny Beach camp near Lovech

Offense: "hooligan", son of a member of the opposition

9 months under arrest and in a camp

Offense: an attempt to escape from Bulgaria

2.5 years under arrest and in a camp

Offense: participant in the anti-communist resistance

3 years under arrest, in a camp and prisons Offense: Agrarian, member of the opposition

3 years and 1 month under arrest and in and political prison

Offense: participant in the anti-communist resistance

In 1961, Zheko was sentenced to death for resistance to the communist authorities. Subsequently, his sentence was changed to lengthy imprisonment.

In 1964, Zheko Stoyanov received an amnesty and was released from the Stara Zagora prison. In order to earn his living, he did hard manual labor, working as a porter, a painter on construction sites, and a miner. For twenty-two years he worked in underground mines.

After the democratic transition of 1989, Zheko Stoyanov entered politics and in 1997 he was elected a member of parliament for the United Democratic Forces. At the age of sixty, he completed a degree in economics.

2 years and 8 months under arrest and in political prison

Offense: dissemination of anti-communist leaflets

After 1958, Alfred was granted the right to travel to Bulgaria, where he spent his summer holidays. There he got to know the new reality of the country and met other like-minded individuals who were dissatisfied with the regime and with whom, in 1968, he distributed printed leaflets against the Communist Party.

Arrested on August 28, 1968, for the distribution of these leaflets, Alfred was sentenced as a spy to fifteen years in prison, of which he served three in the Stara Zagora prison. Following diplomatic pressure, he was released on April 30, 1971, and left Bulgaria. He later returned to illegally take his beloved out of the country, succeeding through a complex and risky plan.

After settling in France, Alfred actively collaborated with groups fighting for human rights in Bulgaria and helped illegally take other political prisoners out of the country. He currently lives in Sofia.

Four years in camps and in forced resettlement

Offence: disagreement with the change of Turkish names to Bulgarian